It is all too easy to picture Britain as being filled with tweed-clad anglers casting to impossibly difficult wild brown trout on gin-clear chalk streams, but, for better or worse, that has never been true of more than a tiny fraction of our fishermen. The chalk streams occupy a large space on the bookshelf, but a small space on the ground, being more or less confined to the country of Hampshire in the south of England. The area is densely populated and although Hampshire is idyllic, it is within easy reach of several major cities, including London, and so the fisheries can charge more or less what they like, and most surely do. If you have read any of the wonderful books written about the chalk streams in their glory days, like Edward Grey's Fly Fishing published for the first time in the 1899, Where the Bright Waters Meet by Harry Plunket Green of 1924 and A Summer on the Test by John Waller Hills also published in 1924, then if you visit England, you will be very keen to take a day on one of these famous waters, but be aware that things have changed. It is estimated that at least sixty-four million people live in Britain, at a very similar population density to Italy, so we face much the same problems that Italian anglers do, perhaps worse, because up to a million Britons fish. Because rod and line angling has been popular in this country since at least the XVII century (there were fishermen here long before that, of course), there isn’t a single square metre of water in the land that hasn’t been fished at one time or another and so it is well known which rivers and lakes are the most productive. Since just about every single piece of land in Britain is owned by someone or other, this means that the only way to get fishing is to rent it off an owner who knows exactly what it is worth, which in the case of the chalk streams, was a great deal even in the 1890s, when the dry fly craze was only just getting started.

Today, it would be easy to pay €550 for a single day’s guided fishing on the River Test. When anglers like the Reverend Durnford, Colonel Hawker and the members of the prestigious Houghton Club fished the Test in the early XIX century, the majority of fish weighed less than a pound, sometimes much less. No-one saw any problem with this, the Test having abundant wild trout in those days and some very large fish were caught from time to time. The technical difficulties inherent in late season fishing meant that few of the Houghton Club members bothered to fish at all after the mayfly season was over, which meant that the river hardly saw any rods after the middle of June, leaving the trout population plenty of time to recover. Until the early 1870s, the majority of fishermen favoured the blow line method, using gently hooked live Ephemera mayflies which were dapped on the water using six metre rod and a very light floss silk line that blew away from them, skipping the fly on the water and compelling them to fish downwind. Then the dry fly method came along, which greatly extended the trout season on the chalk streams, because it made it possible to catch fish on small patterns presented on the surface. The technique became steadily more popular after the 1850s, although it only became common to see anglers using it in the 1880s and 1890s. The dry fly method presented a new problem to fishing clubs because the whole object of the technique was to make it easier to catch trout and to fish right through the season. As more and more anglers took the method up, trout populations came under serious pressure and catches fell. Very conveniently, fish cultists came up with the answer, which was to rear trout artificially and so, from the 1850s onwards, the chalk streams began to be stocked with trout that had been hand reared on horse meat. The practice was widespread by 1870 and had become more or less standard by 1890, and has remained so ever since.

Now the reason why chalk streams are such productive fisheries is that they are full of cool, alkaline water that has been filtered through limestone and which consequently supports abundant plant and invertebrate life. Until the middle of the XIX century, rivers like the Test could be depended upon to have a constant flow of crystal clear water and had dependable hatches of a couple of dozen species of Ephemera, Ephemeroptera and sedges. But as more and more houses and roads were built, pollution increased alongside demand for domestic water, and the hatches began to decline, while the flow began to decrease. By the time Frederic Halford, the author who popularised the dry fly method, started fishing the River Wandle in the late 1860s, the damage was becoming really noticeable. On the Wandle, the Ephemera hatches were almost non-existent and the wild trout population proceeded to collapse half a dozen years later, with the result that the river was having to be heavily stocked by the mid-1870s. It is hard to imagine this from reading Halford’s books, but by the time he began fishing the chalk streams, they were already a highly artificial environment from an angling point of view. All of this makes what happened next all the more ironic. At the precise moment that the chalk streams needed to be treated gently, a highly efficient method of catching trout came along, together with a fast and convenient method of getting to Hampshire from London, in the form of the railway. To make matters worse, the success of the British economy meant that the new generation of business men did not have to work a seven day week and were keen to find something to do in their spare time, for many this was fishing. Halford was one of these men and he inspired a tidal wave of followers by writing a series of very successful manuals about the dry fly method.

The landlords responded to this increased demand by putting up their rents and the clubs had to increase their subscriptions to pay. You can imagine what happened next. Chalk stream trout fishing had never been exactly cheap, because it had always been in short supply, but now it was becoming very expensive. The wealthy men who fished rivers like the Test wanted results and they understood what money could buy, so they put pressure on the committees of their clubs to stock more fish and bigger fish, so they did not have to suffer the embarrassment of going home empty handed. These orders were obeyed, and, as the very famous river keeper of a very famous club remarked about the leviathans he was stocking: "they are there because the members tell me I must put them there, Sir". By now, the situation on most of the chalk streams was nothing like it had been fifty years earlier, there were very few wild trout left any more, fish hatcheries were operating on an industrial scale and the insect hatches were declining steadily due to pollution and the effects of abstraction. The clubs responded to all these challenges by enforcing the use of the dry fly method, which meant that in many, if not the majority of places on the chalk streams, anglers were only allowed to cast upstream, using a floating fly. Even if it was fished upstream, any use of the sunk fly was regarded as the work of the devil, George Skues was given an extremely hard time after he published his two ground-breaking books on nymph fishing in 1910 and 1921, and Frank Sawyer wasn’t treated much better when he published Nymphs and the Trout in 1958.

I am constantly amazed by the chalk streams because most of the clubs and fishery owners still operate as if the calendar had stuck at 1915. Two things have changed, the water is full of stocked rainbows, instead of stocked browns, and in some places, upstream nymph fishing is allowed after June. Big deal, says Herd, but much as I love history and enjoy fishing the chalk streams, this is a case of hanging onto tradition long after it makes sense to do so. The upstream dry fly method rests on the principles that trout cannot see very well behind them, and that the patterns which anglers think of as dry flies are taken as duns; but neither of these theories are true and to make matters worse, they were both proved to be wrong a very long time ago. It is hard to say what trout believe dry flies to be, but since an inspection with binoculars reveals that most are lying awash, they are probably taken as emergers. The few dry flies that aren’t awash are, unknown to the angler, being fished as nymphs, because they have sunk! I have never seen one "riding on its tail and hackle points", as Halford believed them to do, chiefly because it is physically impossible, and it is pointless having to fish dry flies upstream all the time in an era when modern tackle makes it easy to throw slack line casts any which way you can. The reality of the chalk streams today is that, charming though they may be, they are little more than long thin stocked reservoirs protected by a thin veneer of tradition, in my view, the clubs and riparian owners involved would do themselves a favour by throwing the whole upstream dry fly thing away and starting with a new set of rules suitable for this new century. These rivers provide some of the most beautiful fisheries on earth and their spirit would be far better served if the hand of man rested a little more lightly upon them and the fisheries were allowed to be as Durnford and Hawker knew them.

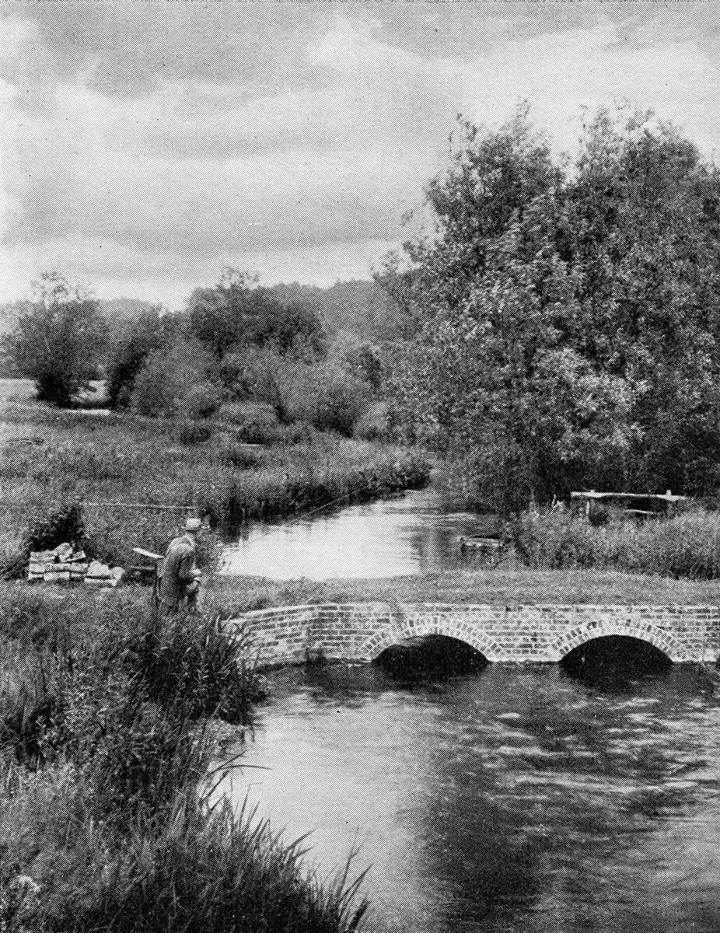

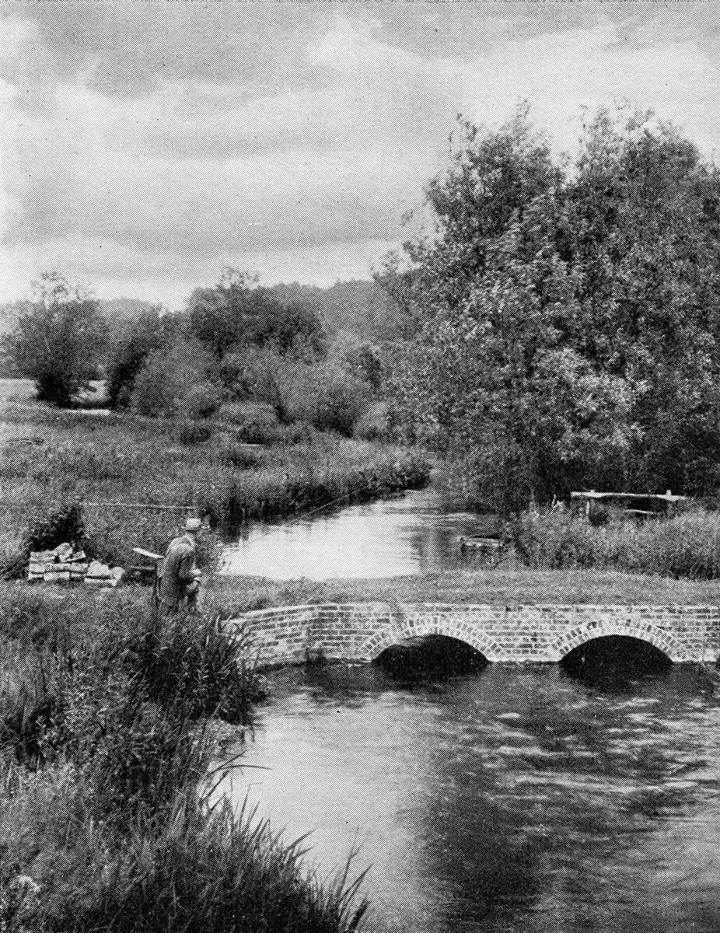

The cover picture shows the river Test in Wherwell, photo courtesy of Fabio Schincaglia.