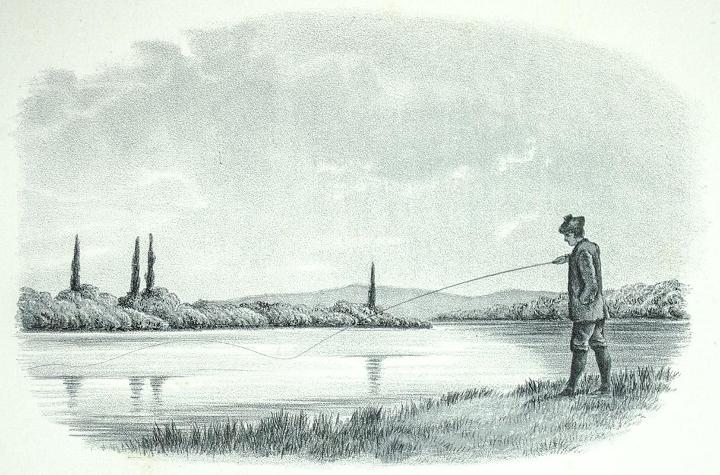

Angling. Somebody, with a pinch of humor, described it as trying to catch, using the best technology can offer, a living being with a brain the size of a pea. And with a high risk of being defeated in this uneven struggle. We, the most evolved creature on the planet at the mercy of a living being driven by primordial instincts. But, despite of this, this is a game which thrilled the mankind since ages. Although, as a matter of fact, it wouldn't have been technically and historically defined a “game”, at least not until the 17th century.Until then angling was intended with only a precise and natural target: to supply protein (Omega 3 were still unknown) or, more simply, to fill up the belly. After the printing of Walton's Complete Angler, angling and more specifically fly fishing started to be considered a gentlemen's hobby and the progression of both fishing tackle and magazines and books about fly fishing gave life blood to this new idea. Therefore, although not being the home land neither of angling in general nor fly fishing in particular, United Kingdom, along with Ireland, can be rightly considered the cradle of angling as a sport. Over the course of time, the combination of the increasing popularity of fishing as a recreative activity, the growth of the population and the simultaneous enlargement of a middle class fostered this development and, together with it the growth of companies specialized in larger scale production of fishing tackle that, until then, were a prerogative of small artisans or , even more often, the outcome of every single fisherman's skill. Unsophisticated rods, hooks made from curved pins, lines made with horsehair, started to be replaced by split cane bamboo or wooden rod, silk made lines, sturdy hooks and later on even reliable reels. All of this came without a precise distinction between angling and fly fishing.

In the English language the hobby of catching fish is defined with a very appropriate term: angling (which comes from the angle, hook), that recaps everything distinguishing the “contemplative” fisherman, he who treats himself going to fish, from professional fisherman. According to Walton, an “angler” was someone fishing, no matter if using live baits and floaters or practicing the complicated art of fly fishing. I cannot deny to love very much the lack of a sharp distinction between the two fishing methods. Having made my first steps on a river equipped with a rough floater and a marsh grass as a fishing rod, I can't help to remember how enjoyable were those summer afternoons chasing after chubs, rudds and small carps in the small pond close to my home. These afternoons were not less enjoyable of those spent now on a river holding a flyfishing rod. Indeed, I dare to say that the carefreeness and innocence of those days gone by, beside the solitude and tranquility enjoyed fully, they were priceless. I am sure that, despite the great passion for fly fishing that lives in me today, I would have no doubt to prefer one of those sunny afternoons with few fish to a modern day passed, alas, elbowing your way casting flies on freshly stocked trout. If only for those boy's scraped knees and for that sun baked still shaggy headed. For this reason, I don't turn my nose up at calling myself simply an “angler”, summarizing all the magic and grace inherent this contemplative sport. That I later choose to devote myself to what we call fly fishing is just a detail. But let's get back to Walton. We said that this book helped to change the way of thinking about fishing and this idea started to catch on in the Anglosaxon society, arriving obviously over the ocean, in North America.

United States and Great Britain continued in the following three centuries to evolve and developing everything about angling and fly fishing in particular that, although practiced since centuries, had its height in more recent times. It's undeniable that the art of fishing with insects' imitation has a very long history dating back to Romans and Macedonians times and with many traces in several European countries and elsewhere, but it's also a matter of fact that proper fly fishing in its most modern aspect with a rod, a reel and a fly line appeared much more recently. In particular, the most advancements in this discipline were made from mid 19th to mid 20th century. Fly fishing in Italy has an even more recent history although fishing techniques using artificial flies were largely used since a long time, for example in the valleys of north western Alps, namely Val Sesia and Val d'Ossola. Italian fly fishermen were mostly influenced by what was happening in British and French markets rather than in North America's even though the very scarce command of english language forbade them to glean from the huge literary heritage tied to fly fishing. If on one hand we cannot deny that the British Isles are the cradle of modern fly fishing on the other hand we must acknowledge that the American contribution to this discipline has been far more than a simple contribution. For some lucky historical, environmental and human coincidences, the Catskill mountains hydrographic basin became around the turn of the 19th century the “melting pot” where the styles, the tackle and the ideas of a modern fly fishing were born and thrived and had huge influence on the European fly fishing scene. The proximity to New York City had necessarily some importance on at least two paramount aspects: having relatively close by rivers and a wide number of pretty well off fond fly fishermen. Travelling in those days was far from being easy as it is nowadays: the train was the nicest mean of transport from NYC to Roscoe, Liberty, Neversink or other villages of the area in New York State. Travelling by car, whenever possible, took very long time on a road far from being as nice as it is today. Most fisherman used to travel by horse and rarely a fishing trip was made in a single day.

The wealthiest ones could afford to sleep in the coziest guest houses spending evenings telling fishing tales quaffing alcohol. But the majority of fishermen used to spend the night in riverside cabins or......under the stars! Even in this circumstances, after frugal meals there was no lack of booze and fishing tales. The outdoor culture, the love for wilderness and go camping has always been much more popular with the American people rather than the Europeans; may be still for a strong legacy with the colonial adventure of the Americans and too much gentrified the Europeans. Fact is that, American catalogues of early 20th century displaying camping, hunting and fishing items were so big and full of wonders (both useful or useless they were) which could keep busy reading hordes of beardless and dreamy teens, and multitudes of respectable professionals who couldn't wait for emulating their ancestors in a kind of survival game in a wilderness no longer so wild. Beside catalogues, manuals on “how to camp in the wild” proliferated. How to travel, what to bring along, how to light a fire or how to survive a Redskins attack, even if the latter were too busy drinking the booze left from the previous night. The growing passion for fly fishing found in the love for outdoor a fertile soil where to thrive. It's a matter of fact that American fly fishing was inspired by British counterpart but the different environmental conditions encouraged Americans to model tackles, fishing styles and techniques adapting them to their homeland rivers.

The forerunner of this process was Thaddeus Norris who in 1864 published a book destined to change the angling concept in America. In this treaty, which encompassed several fishing techniques and tackle to chase after different fish species. Norris included in the book an important chapter in fly fishing, as well as a list of flies suggested to fish in different seasons, emulating in some ways what was made by Alfred Ronalds in his Fly Angler's Entomology. Obviously, Norris didn't miss to point out that flies dressing he described came from his personal selection among models used in Britain, most of them unsuitable for fishing American Brook Trout. This simple selection he made allowed the novices to avoid many flops and frequent attempts with British flies which were imagined for completely different river environment and a very different kind of trout, the Brown Trout, the European trout. Precisely to this refined lady had to be appointed the appellation of Mother of American Revolution, clearly referred to fly fishing. As in every respectable revolution, there's always a combination of triggering factors and the same goes for evolutions. Conditions changes amid spark that triggers the process. As when lightning a fire. The burning matter and the spark, have to coexist. At turn of the 19th century this primordial soup prone to get set on fire already existed: the British influence in fishing gear, the growing spread of dry fly fishing and the related fishing techniques and casting skills (Norris already used to fish with dry flies in his home rivers of Pennsylvania) and, undoubtedly, the continuous blooming of written work and magazines. Only a piece was missing to complete a perfect framework. This piece arrived in February 1883 in the cold cargo hold of a vessel called Werra, set out from Germany which unloaded some 80.000 Salmo Trutta Fario eggs coming from the Black Forest hatchery. Very soon, through subsequent imports from Europe and several stockings, Brown trout spread first in many East Coast rivers reaching the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains. Their better endurance to changing rivers' condition due to urbanization, their faster growth rate and their natural greed, put them in a great competition with the native trout species, Brook trout in the East and Cutthroat in the west.

Overlooking herein to be in favour or against the introduction of allochthonous animals in a territory, it's undeniable that this trout, so prone to surface feeding ( unlike brooks which love the river bottom), changed the American fly fishing permanently. American fishermen were, till those days, wet fly fishermen, usually and with few exceptions, fished downstream. Brown trout brought fly fishing toward a new dimension, that of rising fish, of hatches, of matching the hatch with perfect imitations, of rooster capes with rigid fibers to hold the flies up, but even that of hexagonal bamboo rods of new generations, faster and shorter, suitable for false casts and delicate presentations of floating fly lines. And during all this beautiful trip brown trout went along with men and women who created a world around it made of study, passion and dedication. Of all the celebrities, the one we probably know less about was surely Theodore Gordon, although this thing didn't prevent, despite his mysterious character, he became the icon for whole generation of fly fishermen with a popularity that doesn't seem to fade. The period in which Gordon lived, between 18th and 19th century, can in some way justify the lack of information, partly due to the ease in which these information got lost overtime, especially if one, like Gordon used to, lived a nearly eremitic life with local contacts reduced to a minimum. We don't know nearly anything about his life and the information we have are so peppered that nearly seem to be seeing a plan created by Gordon himself. Some aspects of his life have been known inly thanks to the very few friends who hung out with him in the last years of his life, other come from guess works, suppositions or thanks to that very human habit to enrich legends with other legends. He was born in Pennsylvania in 1854 from a wealthy family and live in Savannah, Georgia, for some years working as an insurance broker. Some letters he sent later to some of his correspondents in the UK confirmed that the bankruptcy of a railways society nearly lead him to ruin and around 1890 he moved with his mom in the NY state. Shortly afterwards he suffered from tuberculosis and it's likely he became weak, both in his body and in his mind, so decided to move in the Catskills Mountain region and there he remained for the rest of his days. On the banks of Neversink River he lived for over 20 years in almost complete solitude, staying in various boarding houses ending his days, suffering from tuberculosis, at Anson Knight House where he died in 1915.

Gordon's dedication toward fly fishing probably has few compeers and it's not easy at all to characterize anybody else who deliberately left behind any kind of social life to concentrate in the study and research about this sport. Although his birth identify him as a cultured and with refined tastes, he became a solitary soul, nearly skittish, tied to a handful of trustworthy friends. Despite his scarce attitude to socialize, Gordon was a prolific writer and his many letters, that was used to send daily form Liberty's post office, kept him in a steady contact with some of the most conspicuous fly fishing celebrities like Halford, Skues and Marston, Fishing Gazette’s editor, great Gordon's assayer; exactly on this famous English magazine of those times Gordon wrote many pieces which counted for a remarkable celebrity even beyond the American boundaries. It's quite likely that without the contribution of his article on the Fishing Gazette, Gordon would have remained neglected forever and ever. These short articles and, above all, the letter sent to the few friends he corresponded with, are the only way to attempt to recreate a profile of this personality. Gordon did not write a single book, and this is a huge pity indeed, but luckily the most of his letters were collected by the historian John MacDonald in a single volume entitled “The Complete Fly Fisherman, the notes and letters of Theodore Gordon”: The love and passion for fly fishing forcefully come to light from these letters, even if a clear feeling of sadness and loneliness comes out of the lines. “The wood stove is my only company” he wrote in 1906. It shouldn’t have been easy at all living for years in those conditions, nearly isolated from the rest of the world, especially during long and cold winters. When reading book or writings about personalities of the past hardly ever the reader identifies himself in a given historical time period.

If we tried to imagine Gordon in his wooden shack on the edge of the wood and not that far from his Neversink, in one of the many winter's cold nights, bent over his vise intent to tie feathers or writing one of the many letters, with the inevitable cigarette dangling from his lips, we would understand how essential were those incessant mails. Those words written in the flickering light of a lamp were his vital lymph. And fly fishing was his palpitating heart. In those years Gordon spent as an inmate, this man of short height with a delicate health, managed to leave a lasting sign in the history of American fly fishing. His beginning as a fly fisher saw him dedicated to wet fly fishing, inspired by Norris' writings and following the tradition of those time. The brown trout coming on the American continent and his undeniable passion for innovation and testing quickly drove him to interpret wet fly fishing in not an exactly orthodox manner. Casting the lure upstream, instead of the classic downstream fishing, he soon realized that his flies could float, they could be dried with false casts and when just tied up and yet not soaked with water they were promptly grabbed by trout especially during hatches. Reading Halford's books about the new theories on dry fly fishing he got seduced by this technique and had the brilliant idea to write to the authors to ask him suggestions. Halford himself kindly replied to Gordon's letter, adding some fifty of his flies and some tips to use them. This letter and those flies are rightly considered a fundamental point in USA dry fly fishing evolution. Gordon in a short while became aware that the structure of these artificial flies could hardly cope with the rough waters typical of Catskills' mountain streams. Believed to be used in the slow waters of England South West, these flies had not the correct making suitable for fast waters, where very important was the quality of the feathers used. Indirectly, Gordon's continuos search for ideal hackles for dry flies started, in the coming years, to the genetic selection of roosters which can produce feathers with stiff and glossing fibers. Gordon did not hold himself back only to change the structure and the materials of English flies dressings , but started to select flies which could match local insects, in terms of colors and sizes.

Among the flies which were ascribed to Gordon, the one that certainly keep his name alive is the Quill Gordon (also called Gordon Quill), still used today, which presents the typical features of the Catskills' flies: peeled peacock quill body, mandarin duck wings that first he tied in a single bunch then he slit them in a V shape ), hackles and tails in medium dun cock hackle (although the original version wanted even tails made with mandarin duck fibers.). Despite his confessed preference for dry fly and for theories on the exact imitation, Gordon never repudiated his past with wet flies, remaining for all his life a real complete angler, never turning his nose to use wets and streamers when hatches were lacking. One of his streamers, the Bumblepuppy, could be considered one of the first imitations which want a combination of feathers and fur. Created for pike fishing the Bumblepuppy showed itself excellent, on smaller hook sizes, for big brown trout. So, Gordon is not only the spiritual father of American dry fly fishing culture but also a great innovator in streamer fishing technique. For the record, the Bumblepuppy is really a killer lure to chase after big browns in the night. Very strongly suggested to try this streamer at the end of a coup de soir or, where allowed, when fishing at night. Just because he had a very wide vision on fly fishing this helped him in avoiding to transform his studies and ideas on dry flies in something too strict, risking to trip in an Halfordian integralism. He never was a dry fly purist like his instigator (Halford) and never Gordon had Halford's conceit. On the contrary, in a given historical moment he got to maintain with his pen pal G.E.M Skues that Halford, with his disdainful blame of wet fly fishing, clearly had trespassed the limit and he lost sight the real essence of the thing. Moreover, he recriminated to Halford of missing that experience that fisherman gets only hanging out in river of various typology. He said Halford was too stuck to chalk streams and not used to rough waters. From his end Gordon, although having spent the most prolific part of his life fishing Catskills' running rivers, had quite an experience reached fishing Pennsylvania limestone rivers. The same rivers that many years later saw the prestigious footprints of Vincent Marinaro.

In the last years of his life, Gordon made a living tying flies that were sold for about one and a half dollar a dozen. It's quite moving thinking that he died nearly without a brass in his pocket and that now his rare flies that seldom appear in the various auctions are sold at very significant figure. But this has always been the destiny of many “artists”. In Gordon's times, we must recall that was quite unusual to tie flies at home, and fly fishermen used to buy their flies from the very few local fly tiers living in the nearby or, those who could afford, used to buy flies that were imported from Europe. Since fly tying could provide the sustenance for a whole family, it's not surprising at all knowing that Gordon was extremely jealous of his skills and of the small secrets related to fly tying, as it happened for many tiers who came after him. None of them loved the idea to initiate other possible competitors. Even Rube Cross, considered “the father” of modern Catskill style (especially in wings and tails structuring) refused to teach to young Walt Dette and Harry Darbee (two of the main future representatives of this style) the secrets of his techniques, even if he was offered a remarkable amount of money. Rube swore to have learnt the art of fly tying from Gordon in person (who he knew when Cross was young) but it's always been considered something quite unlikely, especially by Gordon's closest friends. It's far more probable that Rube Cross had followed the common practice to carefully disassemble flies going backward, checking all the thread turns and all the tying stages of the different materials to understand the techniques Gordon used. A practice that even Walt and Harry used in the beginning of their career.

Among the few close friends surrounding Gordon till he died there was one in particular who had the honour to be allowed to see Gordon while fly tying, although with the promise of not disclosing to anybody what he learnt. This man was Roy Steenrod. Working in Liberty Post Office, he knew Gordon when the latter used to go to bring or to fetch new mail. They soon became fishing and fly tying buddies until the “maestro” died. Steenrod, who later became game and river keeper of the region, returned the privilege of having learnt the art of fly tying becoming the most estimated tier of the area teaching for free to children in the Boy Scouts summer camp. Probably the first fly fishing instructor in the history of Fly Fishing.As mentioned above, Gordon’s person, in some ways mysterious, doesn’t escape from human behavior to daydream on the unknown, sometimes to give an explanation to what cannot be explained. For instance, one of the topics which fascinated his followers, more for morbid curiosity than mere historical interest, was the figure of that mysterious woman appearing in two of the very rare photographs depicting Gordon. In both photos, the two are immortalized while fishing on the banks of the Neversink, the river he beloved, in one photo holding fishing rods in their hands and in the other lazily lying down on the riverbed. Who this woman was is something we don’t know, nobody knows her name, nobody knows if she was a friend, a lover or simply, as he used to call her, “….the best fishing chum…”, his best fishing buddy. The lack of information about his hanging out with women, if not for this mysterious lady, gave space to any kind of guessworks, including theories about his sexual tastes. But to us this detail is definitely irrelevant. We’re far more interested in Gordon as a fisherman, as a fly tier, father and experimenter of the new dry fly fishing in America, nonetheless Gordon as a writer, an aspect of him fascinating me more than all the others. The mail correspondence with Skues are particularly enjoyable and the reciprocal admiration connecting these two friends who never met personally. Having both written for a long time articles for the Fishing Gazzette, they ended up to start a long lasting correspondence and to a continuous exchange of tying materials. Sharing information and exchanging materials among fly tiers is a pleasing and sound habit still today.

Skues himself, in one of his books, melancholically recalls his friend through telling of his last fishing out: already old by then, Skues went on the river with his brother. Eyes and legs were no longer holding him up. The river wasn’t generous with them that day and Skues, watching a trout rising, got from his leather fly holder the only fly remained tied with materials and dressing sent from his friend Gordon many years before. He tied it to the tippet, casted and hooked that marvelous trout. Not as marvelous because of its weight but because it was the only catch of the day, his last trout of a life spent on rivers banks, caught with a fly which connected him with a beloved friend no longer living and who he never had the chance and honour to meet in person. If I was a film director, this would be a beautiful finale. But it was life lived. Gordon passed away many years before, in 1915. At his funeral there were very few relatives and some friend. His body was carried in New York State by train and for a long time traces of it were lost. Many years later, a small bunch of Gordon’s assayers, guided by the famous writer Alfred Miller (Sparse Grey Hackle) tried to find the place were Gordon was buried. They begun their search with kind of a pilgrimage to pay tribute to his memory in the place where Gordon lived his last years, at Anson Knight House on the Neversink. And they did it short before the place was submerged from the dam which was going to be built. Hereafter, by a thorough research they managed to find the grave where he was buried and giving him the respect he deserved. Theodore rests in peace buried along with his mother in the small Marble cemetery in New York City.

Dozens of meters of water now cover the places he loved and where he lived for long years, but his spirit carried on being source of inspiration for those who knew how to enjoy of the real essence of fly fishing, the one Gordon described like this, in these few lines:” The essential need is to find time to go fishing. The true problem is, for many among us, that we’re so concentrated in trying to make money that we lose sight of the best and more innocent pleasures that this old Earth can give us. Time runs so fast after young hood is gone that we cannot fulfill half of the things we’ve got in our minds, and not even half of our duties. The only cautious and reasonable alternative is to allow to other things to let the Essential to go ahead, and the very first of these is Fly Fishing”. On the Catskills, not far from New York City, the lives of many personalities connected by a common interest for fly fishing got linked together; they were fly fishermen, entomologists, fly tiers, bamboo rod makers, writers, fish and hackle farmers and artists. I don’t find a better way to describe the atmosphere of those places, the history they are drenched with and the passion which moved the souls of those men than simply quoting this short passage as told by the sport writer Red Smith. So said Alfred Miller (Sparse Grey Hackle) speaking to the driver who was driving them to the Catskills and who didn’t know the importance of the trout fishing season opening in Roscoe: One stormy April night, three men rode out of the darkness into the streets of Roscoe.

One stormy April night, three men rode out of the darkness into the streets of Roscoe.

“Gentlemen”, said Sparse Grey Hackle, “remove your hats. This is it...”

“This is where trout was invented?” the driver asked.

“Well” said Mr.Hackle “he existed in a crude, primitive form in Walton’s England” “But here” said Mead Shaeffer, artist and angler “is where they painted red spots on him and taught him to swim”

“Gentlemen”, said Sparse Grey Hackle, “remove your hats. This is it...”

“This is where trout was invented?” the driver asked.

“Well” said Mr.Hackle “he existed in a crude, primitive form in Walton’s England” “But here” said Mead Shaeffer, artist and angler “is where they painted red spots on him and taught him to swim”