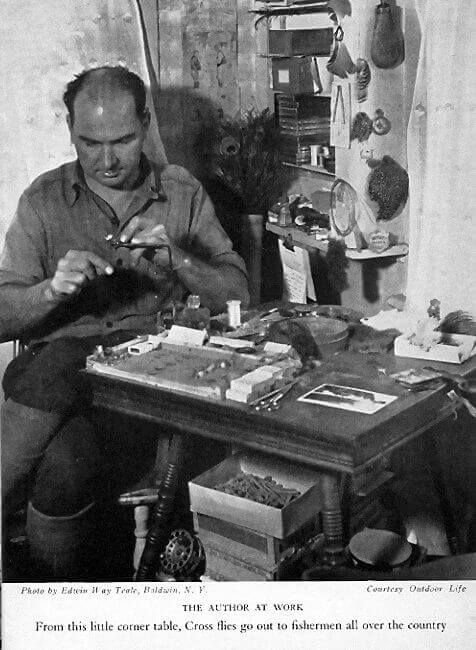

His hands moved swiftly around that metallic hook, for quite some time, maybe hours. With confident gestures, they wrapped silks, coloured threads and mottled fibres, ethereal like bright haloes, retouching with skilful scissors those who did not want to submit to their will. Hands that shaped fragments of past life to create deceptive simulacra of another life. Hands tired and cold that only found comfort in the heat of the cup of coffee resting on the table. Outside it seemed that winter never wanted to end and, despite the different intensity of light heralded the arrival of spring, the cold continued to hammer outside. Yeah, spring. With the spring, the first hatches would arrive and the trout hunters would start to knock on his door more frequently. He opened the first of those letters, calmly. He imagined the content, as of all the others he regularly received. He read those few lines sipping his coffee and letting his hands rest a little. "Dear Mr. Cross, the flies I received are excellent and during my last fishing trip I had the opportunity to prove their effectiveness. Three magnificent browns caught at the Big Bend pool are proof of this. I would be grateful if you would like to prepare three dozen of the usual models in the sizes you recommend for the season. I enclose the amount due to this letter". He carefully folded the letter and placed it under a pile of other papers, in precise order of arrival. On a notebook he wrote down a few lines, numbers and names that would have seemed like incomprehensible graffiti to a layman. Then, with the same calm, the hands lifted a tuft of bright fibres and began to dance again.

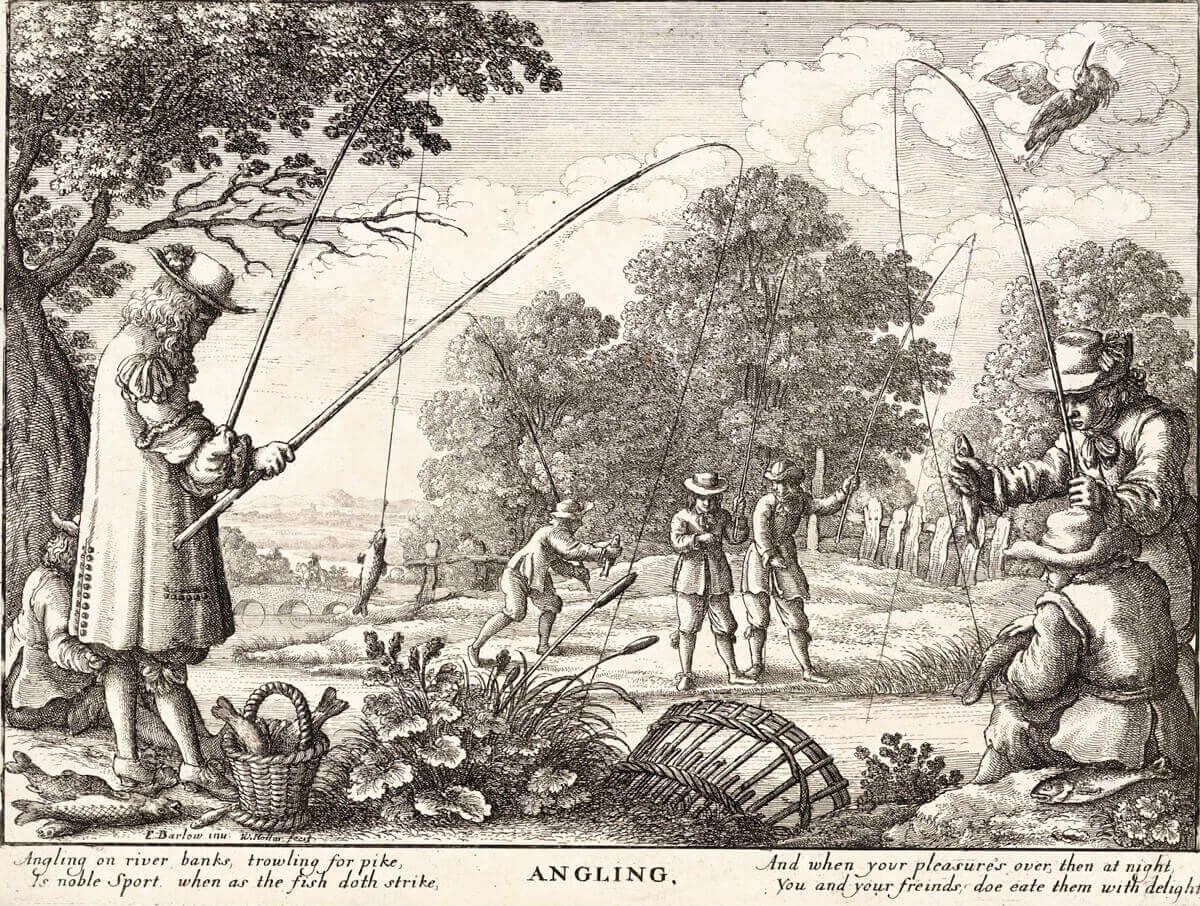

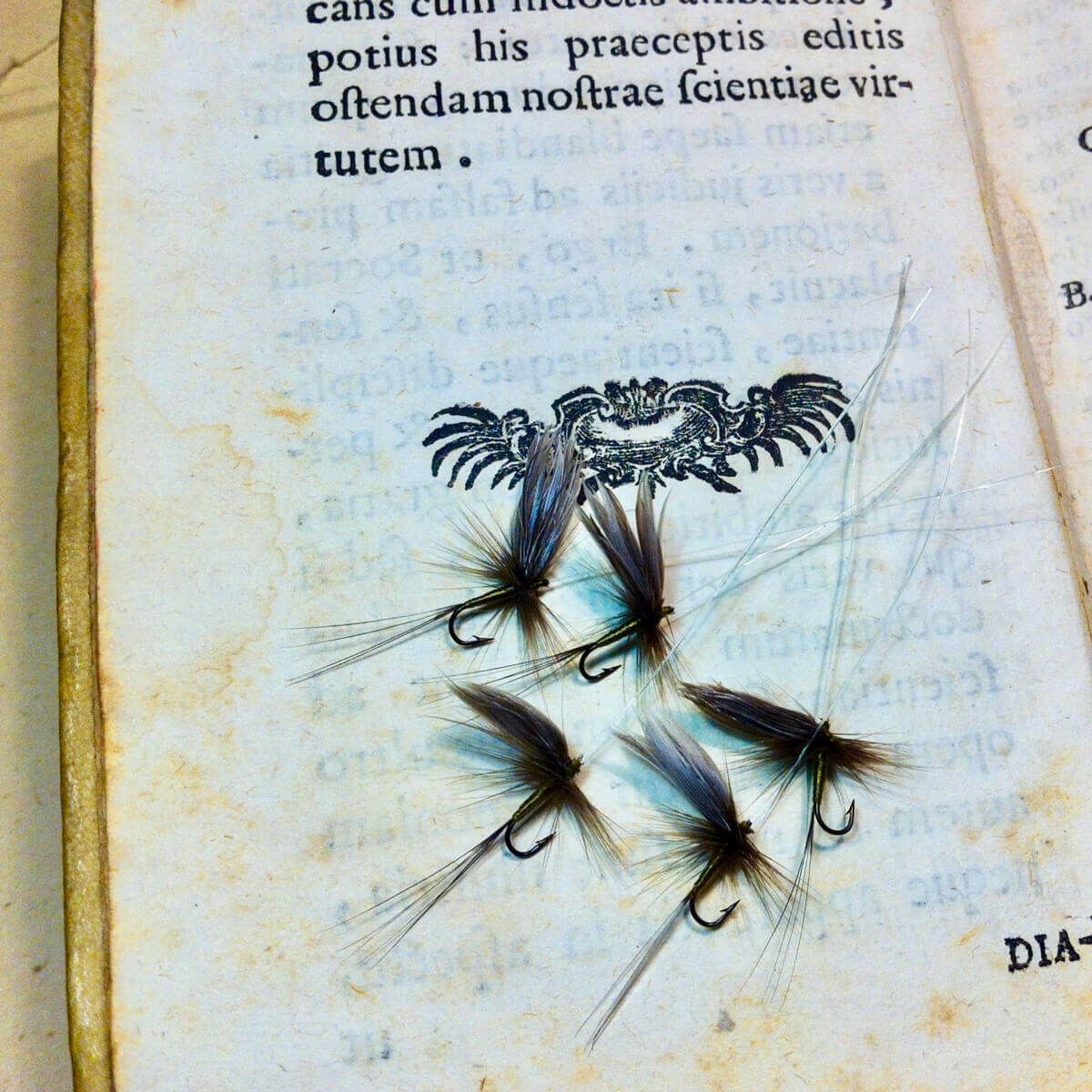

The above, with a pinch of imagination, supported however by the analysis of real correspondence exchanges, could be one of the letters received at the beginning of the last century by one of the various professional fly tiers, in the specific case, of North America. The practice of fly fishing has always necessarily involved the tying of artificial flies, since the dawn of time and without a shadow of a doubt. Hooks, silks and feathers were assembled by human hands and tying flies with what was readily available was common practice until the fly tying materials, as we know them today, became commercially available. Anyone could have realised this by simply looking in the box where a 18th century fly fisherman would have kept his small equipment. For a long time fly fishermen limited themselves to the use of feathers mostly coming from farm animals or hunting preys and using common sewing threads and certainly not sophisticated products for fly tiers. Unless you weren’t one of the lucky fishermen described in the 1850 book by reverend Newland, The Erne and its Legends to which precious silk threads were donated by the "fairies" to tie infallible salmon flies, among which the Jack The Giant Killer or the Parson.

The normal fisherman had only to chase and pluck roosters and hens, maybe from the neighbour farmer, and to subtract from his wife sewing yarn and wool, or rely on the feathers of the hunted birds and with these materials assemble simple flies, mostly submerged models, considering that the dry fly is much more recent history. Probably from the limited availability of materials depended the birth of certain patterns attributable to well-defined geographical locations. One example is the Spanish flies or even the Italian Valsesiana flies. Furthermore, it should not be forgotten that for a long period of time tying arts and technique were not of public domain and the patterns used were, almost inevitably, the result of experimentation and local tradition. And this motivates even more the fact that certain styles remained for a long time bound to limited geographical boundaries. It was probably the press and accessibility to more information to develop a different conception of fly tying. And, above all, the publications containing detailed drawings and colour plates, with hand-coloured flies first and with colour printing afterwards. The simple descriptions of the dressings reported on the first available volumes, sometimes not easy to be interpreted, were not sufficient to allow a correct tying of the flies.

It is interesting to note how the figures of the first professional fly tiers were born almost coinciding with the growth of fishing publications, as well as with the beginning of the marketing on a larger scale of products for sport fishing. And it is quite simple to understand why. We know that fishing in its various facets, including therefore fly fishing, was long considered more a means of making proteins than a true pastime. Fish was food, not sport. Especially because, until a certain moment in history, workers had little time and financial availability and integrating the diet of the family with what nature offered was an understandable need. The contemplative fisherman of Walton was probably more identifiable within the more affluent classes than among the workers in the fields or craft shops that contemplated more the hunger of their stomach.

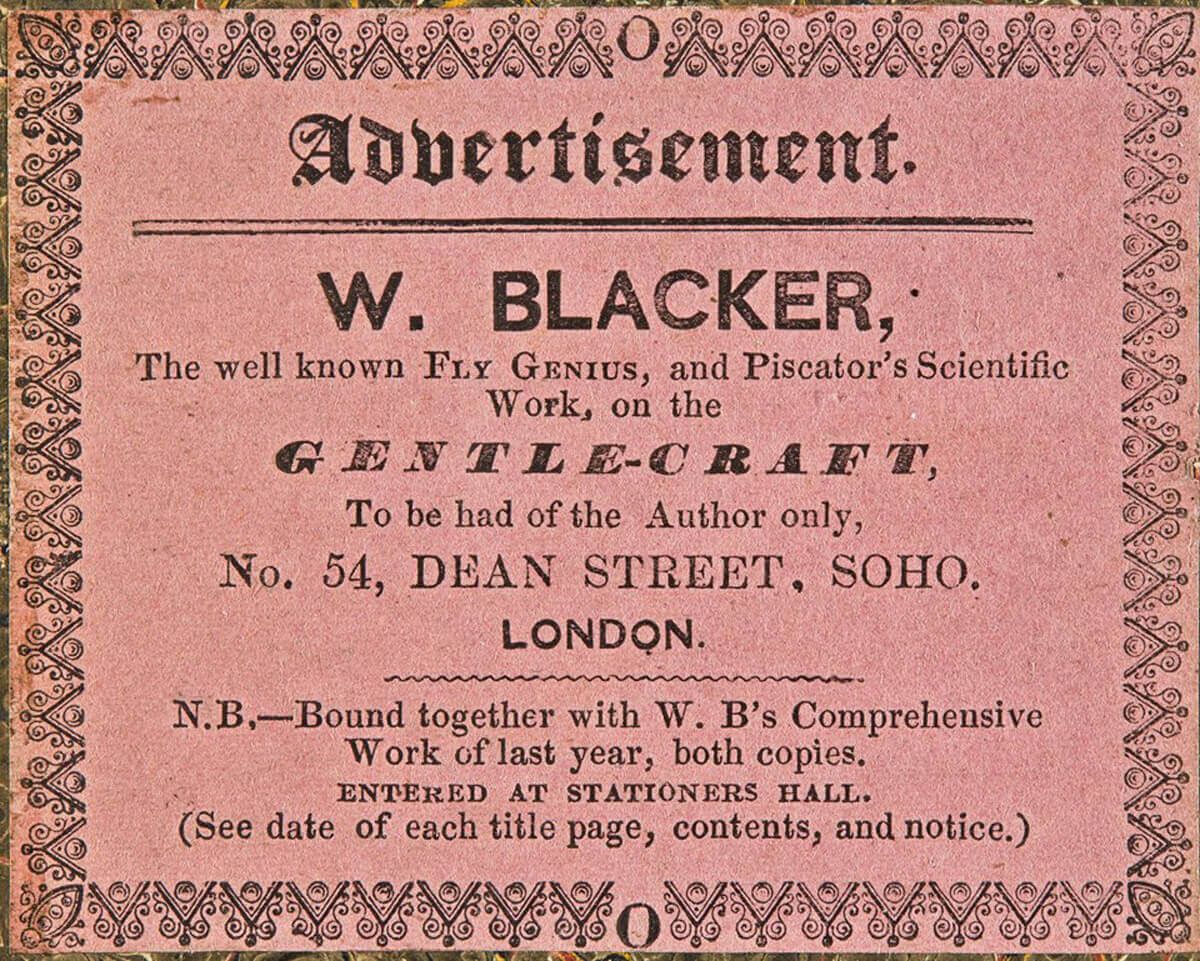

Around the middle of the 19th century, then in the Victorian era, we witness instead the birth of new social classes, with changed economic resources, and a different conception of leisure and leisure time. In this historical period the figure of the sport fisherman began to take shape and the birth of companies specialised in the production and sale of fishing articles was the natural consequence. Often the shopkeepers themselves, once they had accumulated a certain experience in the practice of fishing and sufficient commercial notoriety, delighted in the publication of books and pamphlets showing their techniques and obviously the recipes of the artificial that they considered indispensable. We could mention the Englishman James Ogden who, besides being one of the precursors of the "reasoned" use of the floating fly (even before Halford), with the proceeds of his activity as a professional fly tier, managed to open his own shop and write an interesting volume entitled Ogden on Fly Tying. Another example of commercial foresight was the same William Blacker, owner of a shop in London, who published around the mid-1800 a beautiful book in which he explained, in addition to techniques of construction and dressing of trout and salmon flies, even the difficult art of dyeing furs and feathers. The reputation that came from this book allowed him to do excellent business in his shop and sell their flies at prices almost three times higher than those tied by other competitors. In practice it was an excellent marketing operation of that time.

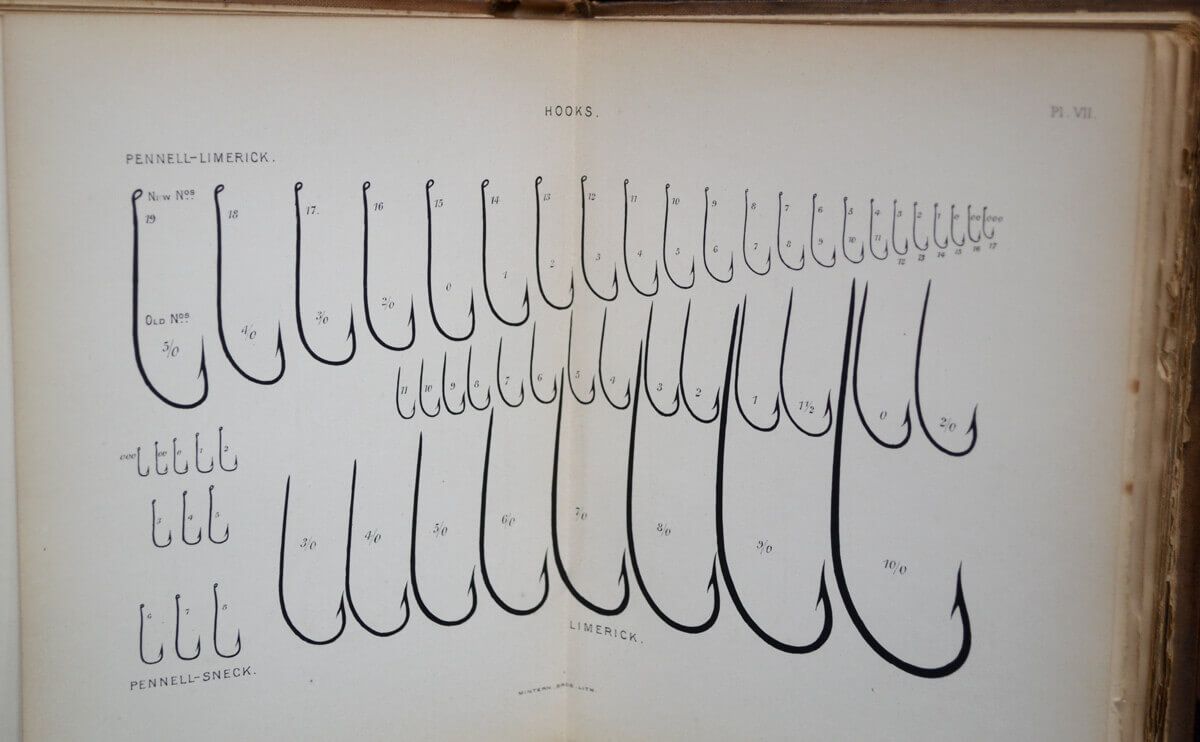

In addition, this was the period that saw the perfection of large-scale production of hooks suitable for various types of lures, production that had been until then almost hand-crafted with all the related problems of quality and availability. And even in this field the tiers-authors of the time did not lose a chance to link their name to certain forms of hooks that were readily advertised on their own writings. It was common practice by characters of the importance of George Kelson, Thomas Edwin Pryce-Tannatt and the inevitable William Blacker, to remain among the most famous. The best quality of the hooks was not a small thing: better shapes, more strength, better resistance to corrosion and rust that lengthened the average life of a fly. We know for sure that even the use of the simple eyed hook played an important role in the development of the dry fly. I agree with those who argue that without eyed hooks Halford would not have existed, or at least his theories would have been delayed for several years.

But you know, innovations are always the result of a combination of factors and triggers. There was dry fly fishing thanks to the hooks, the floating silk lines, the short hexagonal bamboo rods, the false cast and, last but not least, the various floatants to help the flies to keep in the surface. But this is a whole other story. In any case, all this bubbling of innovation in terms of fly tying resulted in an ever-increasing demand for flies to be delivered to the loving care of the beautiful pig-leather wallets or the first beautiful boxes. If we try to identify ourselves with an amateur fly tier of the time we will be able to realise the not small difficulties that then involved the making of a fly. You had to have many materials if you wanted to reproduce the examples shown in the various books, often you had to learn the art of dyeing the plumages, you worked mostly without the use of vise the threads were much coarser than those of today, which required greater care in the control of the windings, and, not surprisingly, the artificial light was not that of today and often tying by candlelight or in front of a window with the right angle was the rule. In fact, many of the old texts never fail to report advice on the ideal lighting to tie easily. About the use of the fly tying vise it is interesting to dwell on the fact that this tool, now considered so essential, it began to be used very late and all tying steps were for a long time performed holding the hook firmly between thumb and forefinger. The first vise were nothing more than small jeweller's clamps, most often held in hand or fixed on a pin inserted into the work table. An example of the first model conceived for the construction of flies is described and designed precisely on the Ogden book, which I mentioned above.

Very unusual, however, is the fact that, as the historian Andrew Herd, lrecounts, Hardy employees continued to tie flies without the use of any vise until 1959. Even in 1969, the year in which they ceased production in the United Kingdom, some Hardy tiers were still making flies in their hands, although this tool had already become in common use. Going back to the inherent problems related to the construction of flies in old times, it is understandable that so many fans began to prefer the direct purchase of the finished fly to having to deal with all the problems described above. Not counting the time saved. Moreover, let's not forget that fly fishing, from a certain historical moment on, became sport accessible to the masses and no longer limited to a few enthusiasts and, as we know, the mass wants to be easy and not too demanding. Even the style of fishing changed over time and thanks to authors such as Alfred Ronalds, Frederic Michael Halford, Leonard West the construction of artificial flies moved to a more scientific approach where the assembly of flies was replaced by the search for the exact imitation of a given insect, in a particular vital stage, to be used in a precise layer of water or, maximum expression, as Halford himself would have claimed, on the surface. Naturally, the imitative research was initially dealt with from the fisherman's point of view and only later did one begin to ask questions about how fish could perceive imitation and this happened above all with the spread of the floating fly.

If on the one hand we can trace the origin of the floating fly to the second half of the 1800s, it is undoubted that the attraction to what happened on the surface is much older history. Any submerged fly, before becoming wet, inevitably had to remain on the surface for some limited time, depending on the weight of the hook used or the richness and quality of the materials and their power of absorption. And in those even short fractions of time something had to happen. It’s easy to imagine that a fish occasionally raised to catch the newly laid fly or when it was still trapped in surface tension? In the writings of Thaddeus Norris or in the notes of the first Theodore Gordon you can clearly read the practice of fishing with submerged flies cast upstream and made to derive without dragging on the surface, when fish were active at the surface. When the dry fly and the search for the exact imitation began to change the approach of fly fishermen, the style and the problems related to fly tying changed accordingly and, combining this to the greater diffusion of this sport, the demand for flies ready to use increased exponentially. The world and the history of fly fishing is full of profiles of professional fly tiers and some of these have been fathers of a real tradition that, in some cases, continues until today. And the lives of some of them it would be worth knowing, at least to have a more complete view of the origins of what we so easily take for granted today.

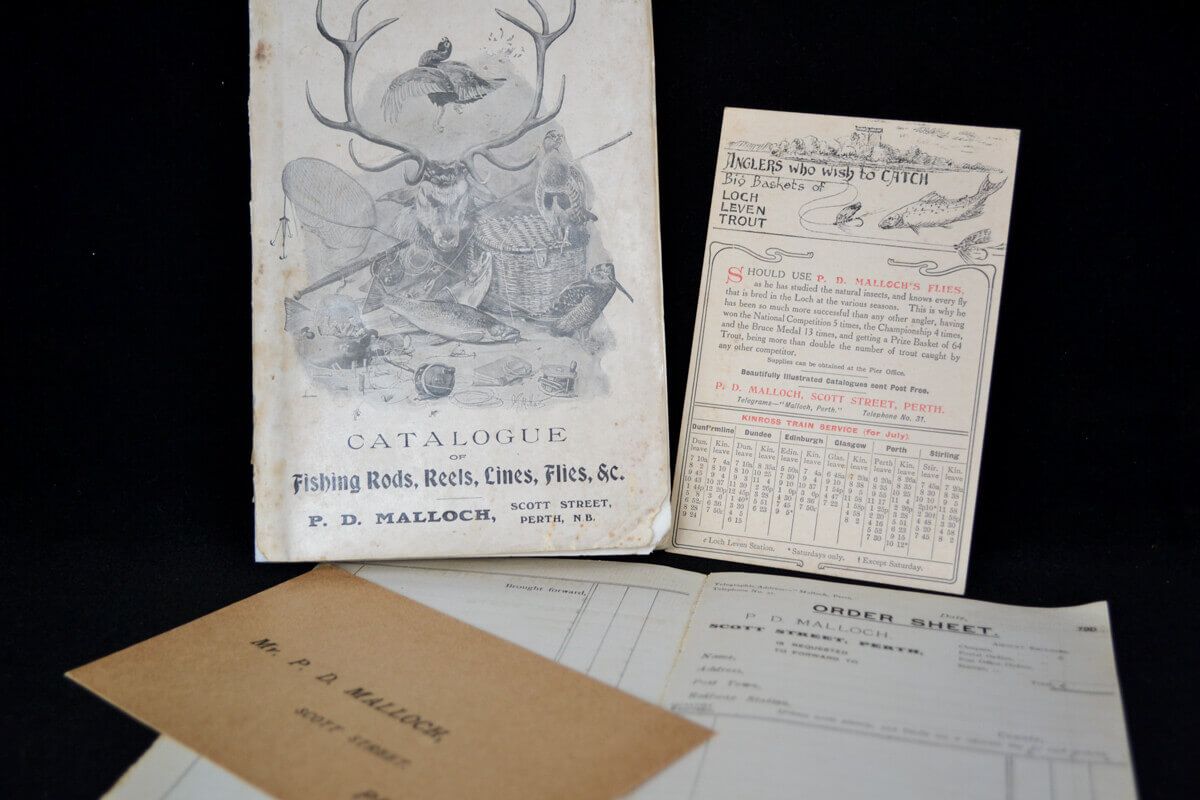

At the beginning of this writing I did not specify that the reference to professional fly tiers is limited, for my personal interest, to the solitary figures, so to speak, and not to the companies that proliferated at the beginning of the last century, giants such as Hardy, Malloch, Herter's, Mill's, Farlow or Orvis produced millions of flies using numerous salaried fly tiers, more or less what happens today in overseas productions of countries like Sri Lanka and Kenya. On the contrary, the ones I love are the profiles of those men and women who made fly tying their main source of livelihood and, in particular, those who linked their name to a style or a fly or simply to the beauty and precision of their creations. Leaving to a possible future script the description of the Anglo-Saxon fly tiers, such as Wright, Blacker and Ogden, I would like here to dwell on the magic of the golden age of American fly fishing. Without denying the enormous influence that, through his writings, a character like Halford had directly and indirectly on the development of a different way of fishing also in the United States, we must premise that the Americans, starting from Norris and continuing with Theodore Gordon, their spiritual father of the dry fly, were able to evolve their style and their technique, avoiding to fossilise their knowledge in the shadow of English literature and tradition. A small revolution or, if we want, a true schism. On the contrary, very often they managed to refine certain concepts and to bring some aspects of fly tying, or of fly fishing more generally, to levels, let me say it, never even reached by the English fathers. The most striking example was the genetic research in the selection of roosters with the optimal characteristics to provide feathers suitable for the making of dry flies and to date the results are more than evident. And this without detracting from the beauty of some plumages such as the Spanish Coq de Leon Pardo and Coq de Leòn Indio or the French Limousines, among other things strictly plucked by hand from live animals.

The first selective experiments had already begun in England on the back of Mendel's genetic studies. Especially when the main source of feathers suddenly began to run low. Paul Schmookler, famous American fly tier, collector and author of beautiful volumes on the history of fly tying materials, told me that most of the feathers used until the mid-XIX came from fighting cocks, introduced in England already at the time of the Roman conquests, from whose names derive many of the names still used by fly tiers today, such as the Blue Dun. The battles between roosters and the resulting bets were a frequent and very popular practice until it was banned in the USA and the United Kingdom in the mid-19th century, causing a sudden scarcity of feathers and an urgent need to find an alternative. And breeding was obviously the most logical solution. But the real search for the perfect feather, especially in the rare grey colour, fascinating appearance, has especially harassed American professional tiers. Starting with Theodore Gordon, with his maniacal selection of the right shade of grey, continuing with John Atherton, an advocate of Impressionism, who could not do without Cree and Badger feathers for his mottled flies and that used to breed his wonderful roosters in the woods of the property, shooting them down with his rifle after having them fly up from his hunting dog, up to Harry Darbee, whose genetic selection is the mother of many of the commercial brands known today, in the sense that many of the packages sold and used today in Europe come genetically from the original stock selected by Darbee.

peculiarity of many of these US fly tiers was therefore the essential link between the commercial fly tying and the breeding of their roosters to which equal care was paid if not more than their own children. After all, the children were a cost while the roosters represented an important source of income. On the backyard of their houses there was almost always the enclosure where the hens were cheating, while the males, for obvious reasons, lived separated in single cages. A fair part of the day was dedicated to these animals and the tasks were, where possible, equally divided among the family members. Funny is an anecdote reported by Alfred Miller, who wrote with the pseudonym of Sparse Grey Hackle and is remembered as the reporter of the Golden Age of American fly fishing, in the book on the life of Harry Darbee, written by Darbee arm in arm with Austin Mc Francis, or perhaps the exact opposite. Sparse tells how Elsie Darbee, Harry's wife and a very refined fly tier, came running out during the night, in slippers, dressing gowns and with a rifle in her arms, and without hesitation she shot between the eyes two raccoons that were trying to feast on their precious cocks. Then, quietly, she went back to sleep like nothing happened. The quality of the hackles has always been at the base of the tying of the dry fly, or at least until someone started to pluck the ass of the ducks in order to obtain CDC Super Select, and from their characteristics of rigidity, length of fibres and flexibility of the rachis depended, and it depends entirely now, the quality of the fly itself. Although the British contributed significantly to the development of fly fishing, they were not particularly active with regard to hackles.

In an autographed and original letter from my collection, Sparse Grey Hackle, speaks without hiding a bit of irony of the low quality of the English hackles and tells Harry Darbee, to whom the letter was addressed, that he justifies this with the humidity, the rain and the bad weather conditions in the UK. And this, beyond the understandable parochialism, could have a fund of truth. In this "adventure afloat" tiers like Theodore Gordon, Roy Steenrod, Herman Christian and Reuben Cross, with their dry flies and their experimentation, went hand in hand with the American people on their journey of emancipation and redemption from the tradition of the classic English submerged flies.

Becoming a professional fly tier was not easy at that time and it was not sufficient to have the strong will to start. We immediately clashed with the obvious and understandable need to learn the technique and this was not disclosed on simple request. Consider that the cradle of the American dry fly was the eastern part of the United States (the West, with its large fur flies that would come later, was still busy with the usual submerged flies) with most of the fly tiers who initially concentrated around Sullivan County on the Catskills. The competition was much feared by those who already lived with fly making and, considering the historical period straddling the great depression, no one revealed their secrets with ease and the first pioneers were forced to untie the flies of other fly tiers to study the turns of thread and understand the technique (just thinking that some of them disassembled the few flies by Gordon still in circulation makes me sick). Feeding a family by selling flies for less than a dollar per dozen was a task and possible new competitors were not logically appreciated. However, consider that around 1940, a dozen high-quality flies could sell between 3 and 4 dollars and that the turnover of a good fly tier was around 4000 dollars a year. An undoubtedly interesting figure that literally pushed thousands of new followers to equip themselves with the necessary to start tying professionally. It is estimated that after the Second World War in the United States there was at least one professional tier in every town or small town that rose near some quality water.

Once the technique was learned, a series of other problems began. The procurement of material in sufficient quantities, the search for the right hooks and, not least, the collection of the first orders. Professional tiers crafted flies for the private sector and supplied the stores in the area, and once their reputation surpassed the boundaries of the county, one could hope for some big order from one of the famous shops in New York or Philadelphia or large cities in general. We have already seen above how the breeding of their roosters allowed to have an excellent control on the quality of the feathers and, of course, a continuous supply of material. Breeders of poultry for food normally used slaughtered animals within two years of life, before they reached the maturity necessary to produce optimal plumages for the construction. And even if the feather merchants could supply sufficient quality packages from India, the problem remained of finding the grey ones, which are still very rare (from India came mostly brown, cream and badger necks). Own breeding therefore became an almost mandatory practice. But the roosters were plucked, at the beginning they were too few and too precious to be killed, and you had to learn to work the scalp if you decided to use or sell, later your whole neck.

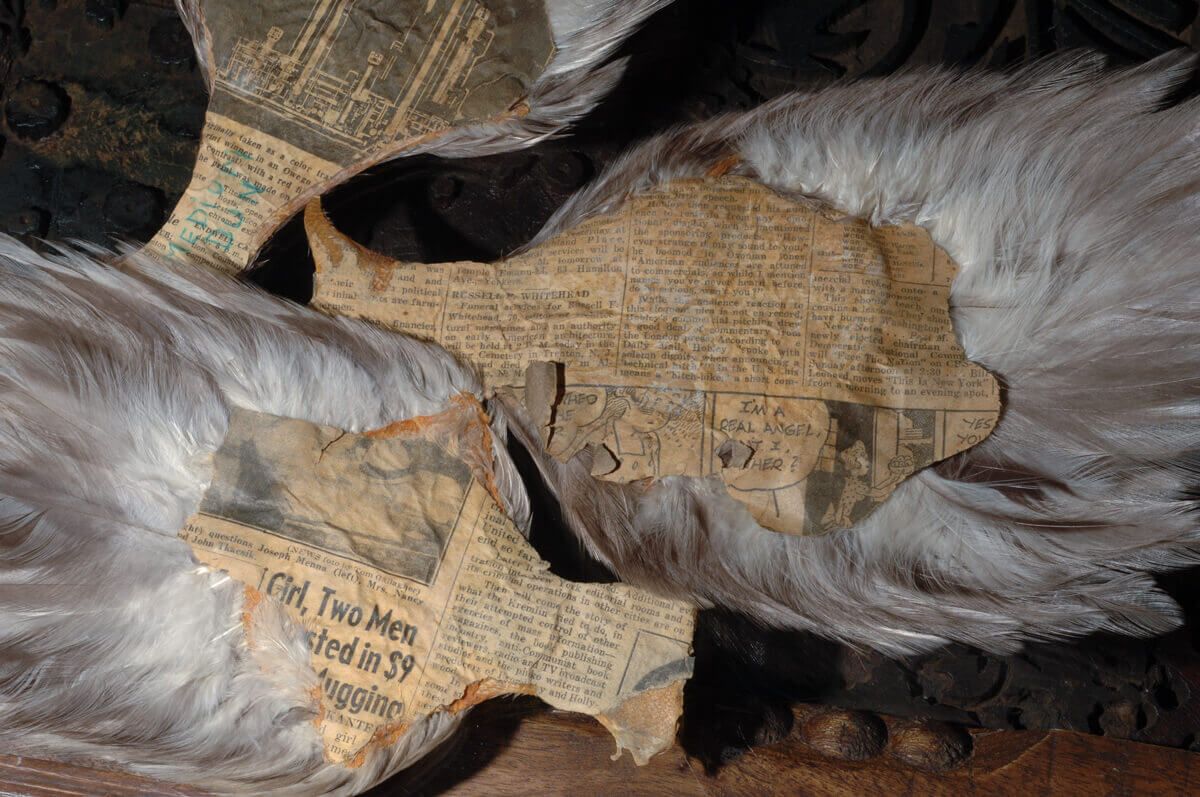

By observing the animals in an enclosure, one could realise that they were in the ownership of a fly tier simply by noting that most of the feathers in hooks size 12 and 14 were missing from the necks of these roosters, the most used at that time, a fly on 16 hooks was already considered a midge. I do not know if these birds were happy to be plucked at regular intervals but, surely, it would have been preferable to live a long life with a plucked neck rather than a short existence with a pulled neck. And, according to what is said, the roosters soon got used to this practice and let themselves be plucked without too much trouble. On the tanning of whole scalps, each had his own technique and some experts and collectors of today are able to determine the origin of a neck examining the cut practiced on the skin. Those of Darbee, the most sought after and rare, are perhaps the easiest to recognise because he used to apply a sheet of the local newspaper on the freshly tanned skin to absorb excess fat. It was fun to read bits of news of the time on the back of the 4 Darbee capes that I jealously treasure three precious natural dun of his famous Andalusian strain and a rare ginger. When the demand for flies began to increase, the only breeding was no longer sufficient to provide certain colours in quantity, therefore producers-breeders began to dye the feathers with aniline and vegetable colours and even to use silver nitrate to recreate the mottled gradation of rare natural greys. All this until Mr. Metz decided to start a fruitful activity focused on rooster breeding for fly tying.

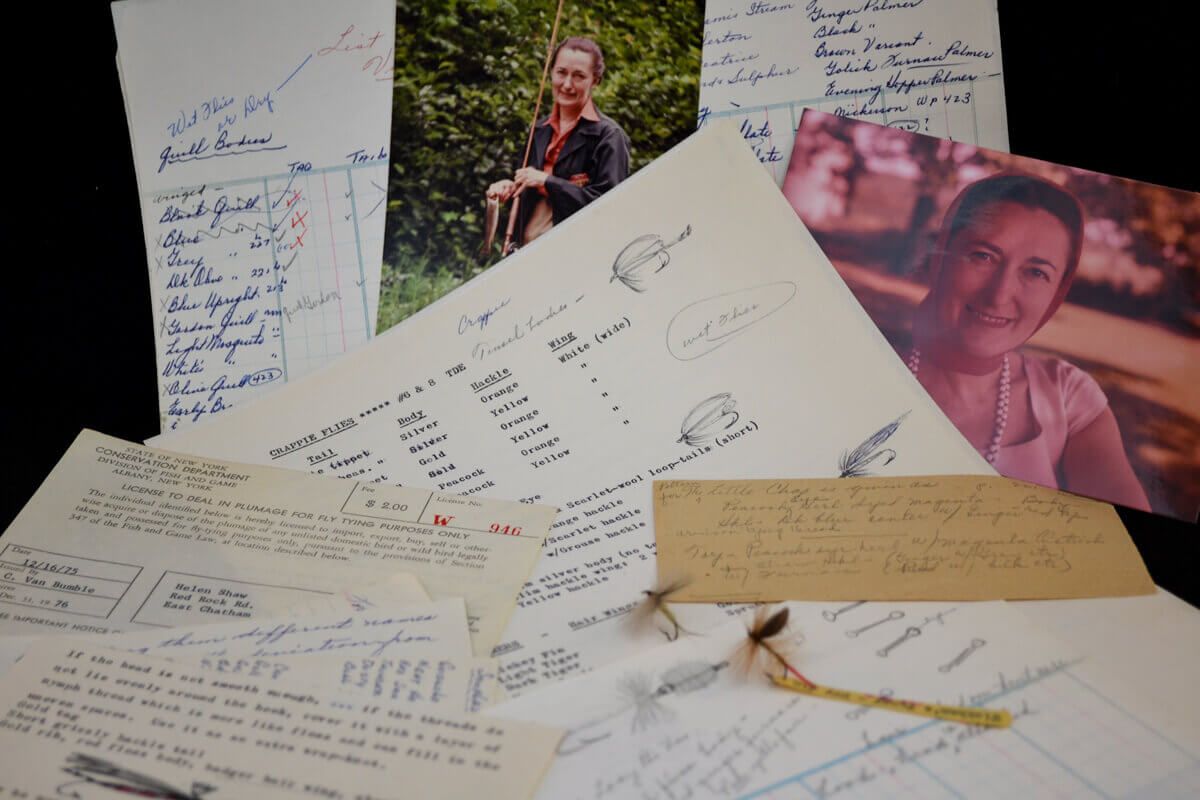

The fly tying tools used at that time were very limited and great importance was given to the manual skills rather than to the help of too much technology which, at times, could even slow down the constructive process. The same tying bobbin was avoided for a long time and most of these tiers favour the direct control of the thread with their hands. Thread that was still largely waxed, either manually or with self-made tools that waxed an entire spool in a single process. A button or other type of pin fixed to the table, a spring or a weight, served as anchorage point to tension the thread during the phases of the making of the fly, when the hands were engaged in other preparations (wings or bodies). Among fly tying couples it was usually the wife who selected the materials, divided the hackle of the right size, while the fly tying was normally divided between husband and wife depending on the models. For example, Walt Dette and his wife Winnie were divided between the Delaware Adams, Conover and the Quill Gordon, while their daughter Mary what a kind lady was dedicated to Coffin Flies and wet flies.

The need to increase financial income and ensure sustenance for the whole family pushed some of these tiers over time, first of all the Darbee family and the Dette family, to open a small shop in their home where they sold fly tying materials, books, and fishing tackle, with a good selection of rods, logically in bamboo, and reels. Considering that the East of the United States was not only the cradle of American fly fishing but also the birthplace of bamboo rod-making, we understand how the relationships between local rodmakers and professional fly tiers were established easily. The Darbees sold in their shop Jim Payne, Ray Bergman proposed the Lyle Dickerson in his catalog, while the Dettes had relations with Everett Garrison himself. And when the time available allowed, between a rod and a few feathers, no one could refuse a good fishing trip together on the waters of some local river, which certainly was not lacking. I remember that the cottage of the Darbee family was almost on the banks of the Willowemoc and that of the Dettes, a little further downstream, in the town of Roscoe, still on Willowemoc, but near the confluence with the Beaverkill Upper Branch, not far from the Junction Pool where the two rivers merge. If you happen to go there, do not miss to try your luck at the Junction Pool. You might be lucky enough to catch the Beamoc, the name comes from the union of the two words Beaverkill-Willowemoc. The legend tells of this large fish with two heads, deer horns and beaver tail that lives in this pool, perennially undecided on which of the two rivers rise.

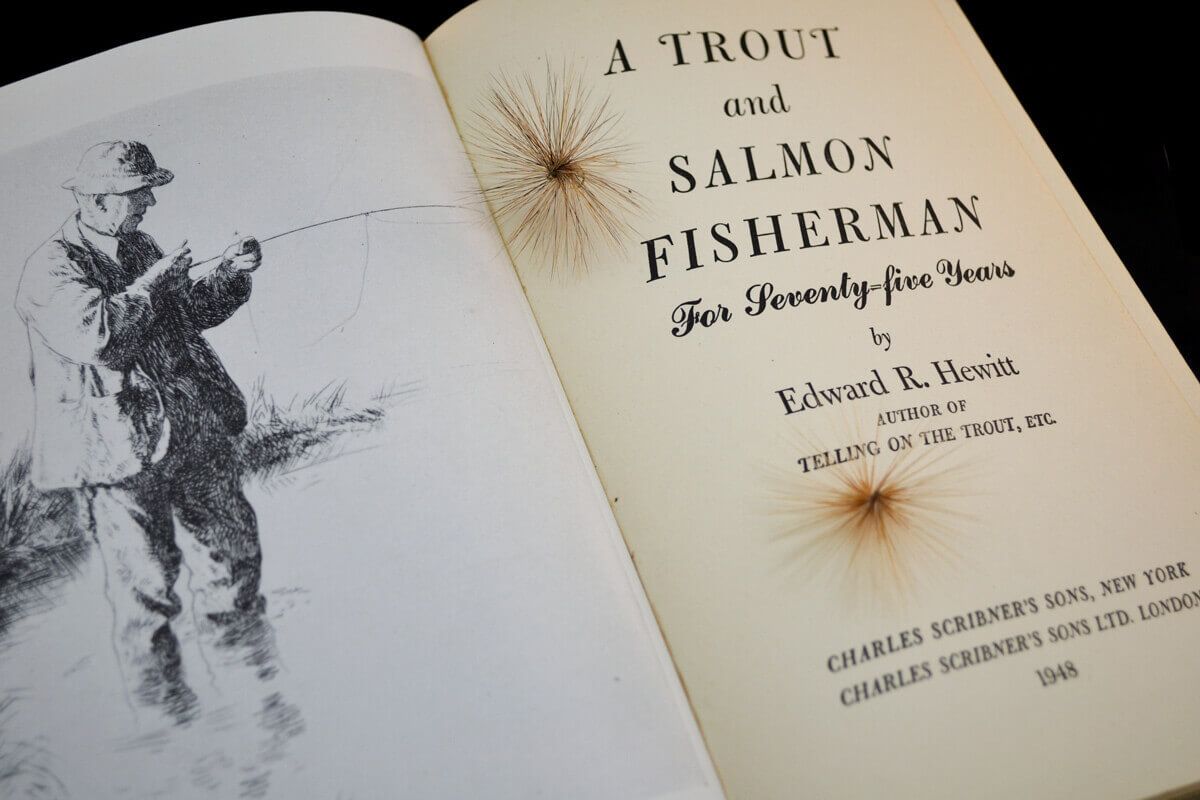

The homes of these most renowned fly tiers soon became a meeting point and a pilgrimage for a multitude of fishermen, including all the best known personalities of the time. They went to these temples of fly tying to buy, to order new flies, to know the situation of the waters of the area and, above all, to have advice on fishing and on seasonal hatches. Even the members of the most exclusive clubs had their preferences and liked to visit one or another of the tiers to whom they also addressed for special orders or for particular changes to the dressings. And considering that many of these customers where wealthy people from the Angler’s Club in New York or the Fly Fishers Club in Brooklyn it was hard to say no to even the most unusual request. It is logical that even the fly tiers themselves had their own preferences in terms of customers and, although the business was still business, they would wander from unexpected visits whenever they could. I remember that Mary Dette told me a few years ago about how her father Walt, despite being a very kind person, used to hide himself smoking in his bedroom whenever he saw Hedward Ringwood Hewitt arriving in his car in front of the courtyard. He waited for his wife Winnie to take care of the client and to return to his construction table only after Hewitt got back in the car.

Hewitt, the inventor of the Bi-visible and Skaters, was a prominent character, rich, famous, an excellent fisherman, inventor, author of books and pioneer of the management of fisheries. But perhaps too far from the simple character of Walt, who nevertheless always gladly fulfilled the requests of the rich Hewitt, always looking for hackles with very long fibres for his beloved skaters. These unique flies were tied on small hooks, often with short shanks, using only an oversized hackle collar made from feathers with extremely long fibres, those that in English are called spade. No tail and no wings. Only hackle rounds. Flies that could reach over five centimetres in diameter. Walt saved the few spades on the necks of roosters just to make the Skaters for Hewitt who particularly loved to fish to the point of claiming that he could catch fish with this fly in any situation. Today these flies are almost impossible to reproduce, except with rooster capes like the one offered by Ewing Feathers, because of the excessive selection of the rooster necks, so full of hackle for small and very small flies but with no hackle above size 10 hooks.

Every professional fly tier always had his affectionate clientele with whom, over time, established a close relationship that often turned into lasting friendship. Several were in the history of fly tying the flies called with the name of a certain character, famous or not, with whom the tier on duty had a close relationship. Like the Colonel Bates by Carrie Stevens, the famous lady fly tier of Maine's long streamers for fishing on Upper Dam's lakes, who named a fly in honour of her friend, Colonel Joseph Bates, a great salmon fisherman and author of various books on the subject. One of the flies loved by Walt Dette was for example the Corey Ford that he named in honour of an American author, well known at the time, with whom Walt had a very good friendship. Speaking of Corey Ford I can not fail to mention the curious fact that this author, in addition to having published articles for 20 years for the magazine Field & Stream, wrote for a long time also for Vanity Fair a series of pieces entitled Impossible Interviews, The impossible interviews "- in which he imagined famous people interviewing others equally known. Like Stalin with Rockefeller or Sigmund Freud with Jean Harlow. I do not know why but these impossible interviews remind me of something very close to us, the Impossible Interview of Fly Line Magazine.

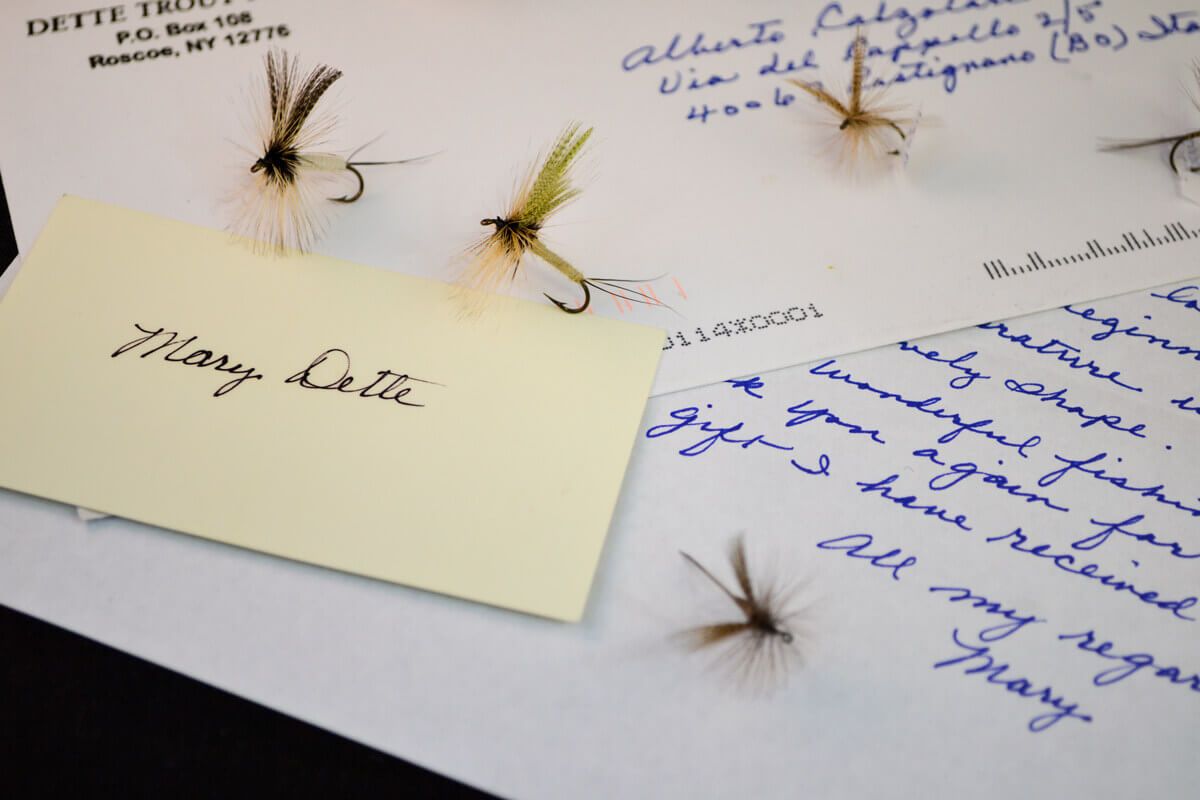

The correspondence between the fly tiers and their customers took place, for obvious reasons linked to the period, by letter and their exchanges of letters are one of the aspects that fascinates me the most. They are small pieces of history, witnesses of an age so far from our, not so much for a temporal reason as for the enormous difference in style and manner, even if only for the elegance of the written form. These letters are impregnated not only with romance but above all with information that can help an attentive reader to better understand the historical period and the figure of the characters in question. And, sometimes, even to give rise to small doubts that can hardly be answered but which will help to increase the charm of the lives of some of these professional fly makers. Lives of characters like Helen Shaw, the Lady Fly tier, who tied flies between the skyscrapers of New York or lonely lives of hard men, like those of Herman Christian, a skilled hunter who, like in the stories about the American frontier, did not hesitate to shoot at a bear peeping from the window of his wooden house, or Reuben Cross, shy and not very social but with golden hands that created some of the most beautiful flies and today among the most sought after and expensive. Or adventures of a whole family as for the Darbee and the Dette, whose tradition has continued until today with his daughter Mary. The art of fly making is like a treasure chest containing stories of fish and waters, stories of insects and stories of men, many of them rendered immortal by their work and their studies. Opening the lid and browsing its contents is always a magical experience and to the skeptics I can only remember that in every fly of today there is always, in some way, the fly of yesterday.

Special thanks to Roberto Messori for permission to reproduce this article by Alberto Calzolari originally appeared in Fly Line Magazine.